Updated March, 2025

How do our sisters and brothers live and worship in Cuba, a land stereotyped for decades as hostile to Christian worship and witness? What can we learn from those members of Christ’s family? The story of their interwoven life and worship challenges and inspires far beyond their borders.

The Christian Reformed Church in Cuba—Iglesia Cristiana Reformada en Cuba—invited me to teach lay leadership in the fall of 2000. From September through November, my fifth and longest visit since 1985, my daughter Jessica, her friend Erica Mol, and I traveled, studied, prayed, and worshiped, marveling at God’s work in Cuba.

Fourteen organized congregations and 120-plus prayer cells and house churches provide spiritual anchors for around 3,500 people—about seven times the number of people in 1985. Most denominations with whom the CRC works in the Cuban Council of Churches have reaped similar harvests. Worship that connects historic biblical teaching to daily life has boldly fertilized God’s Cuban fields.

Growing a Public Witness

After years of dogged spadework, the three-month-long “Celebración Evangélica Cubana” in 1999 fanned throughout the country like Pentecost flames. Leaders of historical Protestant and younger Pentecostal churches won permission to worship in public for the first time in nearly forty years. Starting in April, small village churches celebrated Christ in parks or plazas. In larger cities, services with 1,000 or more praised Jesus in amphitheaters. In several provincial capitals, more than 5,000 Cubans hungry for the gospel of the Man who multiplied two loaves and five fish filled baseball stadia. Finally, on the third Sunday in June, 120,000 Cubans worshiped in Havana’s “Plaza de la Revolución.” President Fidel Castro was among them. Was foxy Fidel merely giving evangelicals equal time for Pope John Paul II’s 1998 visit? The more complex and compelling truth shows that God’s mysterious Spirit keeps blowing in Cuba more publicly than ever.

Youth Worship

Arriving at Havana’s José Martí International Airport, we ride with Pastor David Lee 130 kilometers to Jagüey Grande. By 8:30 p.m. we enter the weekly youth worship in Cuba’s largest CRC. “Youth” in Cuban churches means ages thirteen to thirty. Generations suffer fewer gaps than we accommodate in North America.

About fifty people gather, sing for a half-hour, divide into prayer groups, and then re-gather for another hour. Pastor Obed Martinez, his wife, Alina Aguila, or an older youth presents a biblically guided lesson on life-forged issues. In 2000 the group was studying Christian sexuality, a course developed by the Latin American Council of Churches. As Cuba’s representative to that body’s executive, Obed travels to South or Central America several times annually. He always returns with new songs or courses to share with the congregation, denomination, and other Cuban churches.

Cuban Christian youth know their villages or neighborhoods well. Most schoolmates never attend worship. Over the years, Christian students have quietly and with great determination gained respect from peers and teachers. About twelve Jagüey Grande CRC youth are university students or graduates. Others are high school students, office managers, barbers, sugar mill or citrus or agricultural workers, or soldiers. (Two years of military service are mandatory for male high school graduates). Ten years ago most did not know Christ. Now they do, because once a church member or worship service drew their attention to Christ’s Spirit in daily life.

Young Cuban Christians find quiet, daring ways to integrate life and worship in a climate once hostile to them. On my first visit in August 1985 to speak at a weeklong camp, thirty-five young people attended. Now the camps stretch over a month with 450-plus youth taking part. More and more unbelievers are feeding on the Bread of Life growing from Holy Spirit yeast. That’s all in preparation for the Wedding Supper of the Lamb, for people from every tribe and language and people and nation.

Prayer Worship

Wednesday about 7:00 p.m. Nery Rodríguez enters the Jagüey Grande church to prepare in solitude for leading evening prayers. During our stay, worshipers were praying and meditating through Revelation. Around 8:00 p.m. fifty-some people arrive on foot or bicycle. Lasting more than two hours, the meetings mix community news with prayer and worship. After the gathering hubbub, people sit in wood-slat pews. Whenever possible, I take a solid-seated folding chair; at least I can stand after dismissal instead of painfully prying myself from the slats into which I end up woven.

When Nery stands, the worshipers quiet. After minutes of silence, splendid play-by-ear keyboardist Yosmany starts improvising softly. Soon a few people quietly sing or hum to melodies played on a new synthesizer (a gift from my Thunder Bay congregation). Presently Nery opens with prayer, then leads a number of songs. Among them we sing internationally familiar “Alabaré,” its text quoting Revelation 5.

After the singing, Nery reads and introduces that chapter for the small prayer groups. Embracing the text, she recommends that all prayers weep like John until they experience Christ’s worthiness and power. That power, she reminds us, was shown in his once-for-all sacrifice. It lives still in his weeping and believing people. “Faith shines in our willingness to live enthusiastically for the good of the nation, to praise God. Now go, pray through Revelation 5.”

For the next forty-five minutes, Nery’s reflections help our group weave prayer into daily life. As prayers take off from Revelation 5, some people weep. Parents beg Christ to lead their children who attend state-run residential schools. Two university students pray that Christians in Cuba and in the United States will sacrifice boldly to end the economic blockade. One deaf member signs thanks to God for the recent sign language course taken by more than thirty people from different churches—a course that was jointly funded by the Cuban government and several international ecumenical bodies. Ten years ago, such a project would have been unimaginable. Church and state are strictly separated in Cuba, but Christ sneaks in like a bold thief anyway.

Along Comes Sunday

As in many churches, Sunday school starts at 10:30 a.m. and evening worship at 8:00 p.m. The Jagüey Grande church, built in the 1950s with help from local congregations in Grand Rapids, Michigan, holds 150 worshipers on those dreadful slatted benches. But from 1960 until the mid ’70s, fewer than fifty attended. Now the place overflows twice a Sunday. Persistent prayer, work, and worship, in approximately equal measures—all wrapped in mysterious grace—produced changes that were decades in the making.

By 10:30 a.m., between 170 and 250 people squeeze into the Jagüey Grande church; often another 50 mill outside. Loudspeakers at a farmers’ market next door belt out salsa. (Some believe that is deliberate harassment—not that they much mind; many Christians thrive on salsa and merengue.) Lay leaders teach songs in pre-class worship, take attendance, make announcements. Attenders are asked to hold up Bibles. More than half own Bibles now; twenty-five years ago the congregation owned only five or six tattered Bibles. Canadian tourists started bringing gift Bibles in the 1980s. In the 1990s European Bible societies cooperated to ship more than 500,000 Scriptures and other Christian books. Similar shipments continue.

Before classes begin, offerings are gathered for benevolence and missions. Classes head to side rooms and the third floor of CRC headquarters a block away. An hour later they re-gather to hear tallies of attendance, Bibles, and offerings. Totals in Cuban pesos are announced, plus foreign currencies donated by frequent guests. After they close Sunday school with prayer, members go home for an afternoon of rest, choir practice, baseball games, or visits to hospitals and outlying missions.

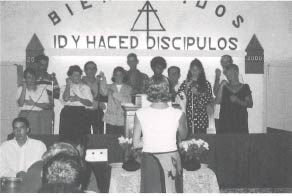

By 8:00 p.m. it’s dark, the afternoon heat slowly moderating. As church doors open, people again gather for worship a la cubana. A combo of drums, keyboard, acoustic and electric bass guitars, trumpet—and flute, if we’re lucky—starts jamming. I recognize some hymns, rhythms Latinized, harmonies improvised. Usually 150 people attend, sometimes up to a hip-squeezing 225. As a worship team mounts the elevated platform, the congregation focuses, their din muffling slowly.

A suddenly announced prayer of preparation quiets us. That familiar rite reminds us that the source and goal of worship is Christ, who crosses borders and breaks down walls. Pastor Obed greets us in God’s name, urging us to greet each other. So we do—all of us, for fifteen minutes. As the worship team starts singing, worshipers find their places. Most songs come from the Cuban songbook Cántale a Dios, published in Matanzas, Cuba, in cooperation with Christ for All Nations in 1996. We sing “O Jehová, Omnipotente Dios” to the same melody as “God of All Ages, Whose Almighty Hand.” If songs aren’t in the book, I feel right at home, as eager young overhead operators do their best to focus the projector and—after several hilarious tries—place the text right side up. Some things are the same all over the world.

My daughter Jessica took the sign language course mentioned earlier. Several students were deaf members of the Jagüey Grande CRC. Tonight, Jessica leads the fifteen-person deaf choir silently signing “Grande y Fuerte es el Señor Mi Dios” (“Great and Mighty Is the Lord Our God”). The congregation sings two stanzas as the choir keeps signing. On one stanza, only the keyboardist accompanies the signing choir. The church echoes in deafening, awe-filled silence and thanks to God for barriers broken between the hearing and deaf worshipers. God’s healing power strikes us dumb. Christ the Word urges us to hear with new ears, through many tears.

Soon we recite (and some sign) the Apostles’ Creed. Obed reminds us that this symbol of faith ties us in Cuba to people we were separated from for years. Shivers shoot up my spine; I was one of those separated persons. When we respond with “Gloria demos al Padre,” I’m so rattled I can’t decide whether to sing “Glory Be to the Father” in Spanish or English. I mix it up hopelessly; no one notices.

After Marely prays for the Spirit’s leading, she reads Hebrews 11. Pastor Obed has been preaching through Hebrews for two months. He introduces the “heroes of faith” as vessels of grace, not flawless exemplars. “Still today, we’re nomads like Abraham, laughing doubters like Sarah, cheats like Jacob, outcasts and foreigners like the prostitute Rahab. Yet all belong to Christ’s sinful and saved family. God in Christ rescued us, urging and provoking faith in twisted, now forgiven, hearts.” Obed’s message resonates with the Heidelberg Catechism’s themes of sin, salvation, and service.

Obed lingers on Hebrews 11:30. “Israel’s God-forged belief tumbled Jericho’s walls. Our nation’s thirty-five-year-old walls have only started to tumble by faith.” He names walls, some tumbled, others cracking, others still rock solid: “We worship freely here—but outside? We still need written permission. Pray in faith. Governmental agencies have justly permitted us to rebuild several churches and parsonages—but others are falling apart. We only dream vaguely of Christian broadcasting and publishing. It took years to obtain permission for a seniors lunch program in [nearby] Agramonte—but many more there and elsewhere need both lunch and the Bread of Life. Keep praying. Amen.”

This is worship in Cuba—often familiar, yet startlingly new, daringly engaged in society and always grounded in Christ’s gentle lordship over persons, church, state, and world. Faithful worship everywhere points us to and beyond walls Christ breaks down, so God’s people can stand up for Jesus with joy, beauty, and courage until he returns.

For over forty-two years of living in the Cuban Revolution, lay leaders and the few ordained pastors in Cuban churches have mined Christian tradition with creative and daring contextualization. Worship engages daily life, even—or especially—when risky. As a result, many Cuban churches have managed to redeem significant parts of a society that some had declared outside of God’s embrace. Through prayer and work and bold, imaginative thinking, Cuban Christians have poured hearts, minds, and bodies enthusiastically into every nook and cranny of their lives, churches, and nation.

Though it’s impossible and foolish for us on the mainland to import wholesale orders of worship, practices, and techniques, I offer two whimsical “recipes” (see below) that attempt to show the heart of Cuban worship. Some of the songs I’ve mentioned in the article are available both in Spanish and English. Yet week after week in Cuban worship I heard new Bible songs—simple, singable, most probably not long-lasting, but all fitting the day’s need.

May worship committees all over God’s kingdom freely claim God’s space in our world and keep worship hand in hand with daily living.