Updated May, 2025

Sing! A New Creation includes a delightful little sung meditation by John Bell of the Iona Community that has as its opening line, “Take, O take me as I am; summon out what I shall be” (SNC 215).

I have used this many times in worship, often as a sung refrain in a prayer of adoration and confession. I especially like what it suggests about our humanity: We are accepted by God not on the basis of who we are (the “God-accepts-me-just-as-I-am” mentality), but because of who we are in Jesus Christ and what we might yet become, or are summoned to be in him. Being in Christ, the truly Human One, is the basis of both our acceptance and our transformation.

There is a strong echo here of Paul’s exhortation to the church in Colossae to set our minds on things that are above, for we have died, and our lives are “hidden with Christ in God” (Col. 3:2-3). This is ascension talk.

Humanity Infused with Hope

The Christian life is not merely a matter of following the example of a person who lived two thousand years ago. Rather, it’s about being drawn by the Spirit to share personally and corporately in Christ’s ascended life and humanity, and in so doing finding ourselves clothed with “a new self, which is being renewed in knowledge according to the image of its creator” (Col. 3:10).

“In that renewal,” Paul goes on to declare, “there is no longer Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian and Scythian, slave and free; but Christ is all and in all” (Col. 3:11). In other words, being in Christ involves being part of a new reconciled and reconciling humanity, in which the divisions and inequalities that characterize the old humanity have been superseded. When we are in Christ, our humanity is infused with hope, and we are able to declare with Paul: “It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2:20).

Whenever I ponder this uniquely Christ-centered and Spirit-shaped perspective on human personhood, my mind turns to Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1-10). Drawn toward Jesus out of curiosity, this despised tax collector finds himself ushered into a new reality that is utterly liberating and transformative, with remarkable results—he pledges half his money to the poor and promises to repay fourfold those he has defrauded.

It seems to me vitally important that Christian worship give robust liturgical expression to this theologically derived anthropology. In so doing it will inevitably presume the doctrine of the ascension, for it is the ascension that provides the basis for affirming the continuing significance of the Incarnation and the vicarious humanity of Christ.

In light of this affirmation, the Incarnation should not be understood merely as a necessary prelude to the events of Easter. Rather, it has atoning significance in and of itself and finds its completion in the ascension. The ascended Christ is the One in whom, with whom, and through whom our reconstituted humanity has been lifted before the throne of grace. Through the activity of the Holy Spirit, we are joined to Christ and lifted with him into the presence of the Father and brought to share in the life of this triune God.

Every time we recite the sursum corda (“Lift up your hearts”; see RW 82) in the liturgy of the eucharist we give voice to this reality. The lifting of the congregation’s hearts is to be conceived as our being brought by the Spirit to participate in the perfect praise and adoration that Christ the High Priest offers on our behalf. This is how Calvin conceived of the real presence of Christ in the sacrament. Not, as the Romans taught, in the transubstantiation of the elements, but in the act of being lifted by the Spirit, through the Son, into the presence of the Father.

Our Ascended Intercessor

Thus understood, the doctrine of the ascension provides the basis for talking about the ongoing work of Christ in worship and prayer. In the book of Hebrews, Christ is portrayed as the great High Priest, the mediator of a new covenant, the leader of worship, the true intercessor, the pioneer and perfector of our faith.

What this cluster of titles and roles suggests is that the work of Christ did not end at Calvary. It is ongoing. The ascended Christ continually offers worship to the Father in our place and on our behalf; he continues to pray for the world he has redeemed in suffering love.

This last point is most important for helping us understand the basis for intercessory prayer. It is interesting to note that Diebold Schwarz, one of the forerunners to the Genevan Reformation, located the prayer of intercession within the eucharistic prayers of consecration and thanksgiving, thereby acknowledging that intercessory prayers are inextricably linked to the intercessory work of Christ in his role as High Priest. Calvin maintained this practice.

Of particular significance here is the idea that in prayer the Church does not merely participate in the benefits of Christ’s work—it participates in the work itself.

This was a point emphatically reinforced by the nineteenth-century South African pastor and evangelist Andrew Murray. In his book With Christ in the School of Prayer, Murray described Christ’s ascended life in terms of an ever-praying life which, when it descends and takes possession of us, constitutes in us too an ever-praying life. Our faith in the intercessory work of Christ, therefore, must not only be that he prays in our stead when we do not or cannot pray, but that, as author of our life and faith, he draws us on to pray in union with himself. In prayer, and through the work of the Spirit, we seek nothing less than the mind of Christ and commit ourselves to the way of Christ.

Christ, the Eternal Sacrifice

If the doctrine of the ascension provides a basis for talking about the intercessory work of Christ, it also provides a basis for talking about his eternal self-offering. In the Church of Scotland’s 1940 edition of Book of Common Order, the liturgy of the eucharist included a reference to “pleading Christ’s eternal sacrifice.”

The authorship of this phrase has been traced to the internationally renowned liturgist of the time, William Maxwell, who appeared to be drawing on the insights of the nineteenth-century champion of liturgical reform, William Milligan, and his son, George. Along with John McLeod Campbell, these pivotal figures in liturgical reform argued that Christ’s offering to the Father was not confined to the offering of his life at Calvary two thousand years ago. Rather, in light of the ascension, it is deemed to continue.

The ascended Christ is the one true worshiper in whom, with whom, and through whom, and by the Spirit, the Church’s own meager offerings of praise and thanksgiving are joined, perfected, and offered to the Father.

A worship service that portrays the offering, duly collected and dedicated, as a means of supporting the life and mission of the Church is a worship service with a vastly reduced understanding of the Church’s participation in the eternal self-offering of its Lord. Even when the eucharist is not celebrated, the offering should be understood eucharistically in terms of being united by faith with our great High Priest’s eternal sacrifice, that we may plead and receive its benefits and offer ourselves in prayer and praise to the Father.

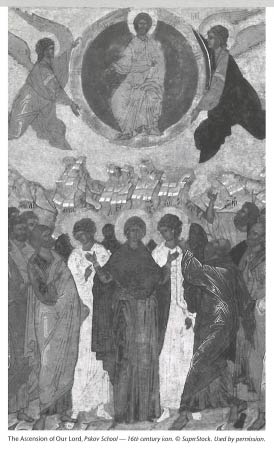

In summary, the doctrine of the ascension is essential to understanding the nature of worship and prayer, the ongoing work of Christ, and the nature of human personhood. Belief in the ascension flows from a trinitarian doctrine of God, and it commits one to belief in the vicarious humanity of Christ and his role as High Priest. That Luke closes his gospel and opens his book of Acts with accounts of the ascension shows its importance in linking the person and work of Christ (as narrated in the gospel) with the activity of the Spirit (as narrated in Acts).

Falling as it does between the more prominent festivals of Easter and Pentecost; the Day of Ascension is easily overlooked. It does not have a church season named after it, but that should not render it any less significant.

In the risen and ascended Christ our humanity—assumed, sanctified, and redeemed through the cross—has been lifted into the innermost presence of the triune God. For now, the full extent of this reality is hidden from us, but it is nevertheless something into which we can grow.